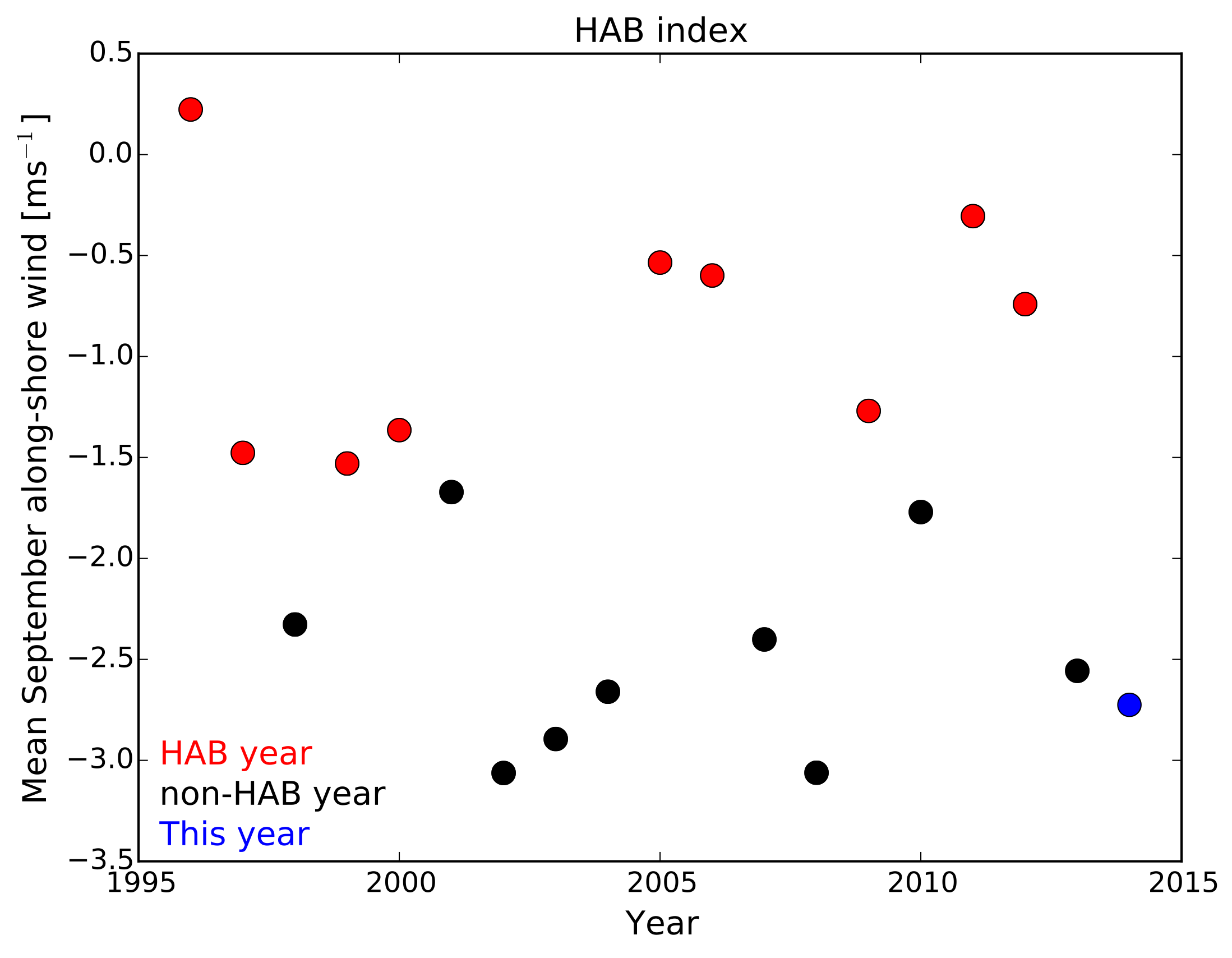

Colleagues and I are predicting that there will be no severe harmful algal bloom in Texas waters for the rest of the season.

Previous research indicates that the measured winds in September at Port Aransas, TX, are predictive for whether or not a major harmful algal bloom will occur that year.

A harmful algal bloom caused by the phytoplankton Karenia brevis, colloquially known as red tide, can have serious human and marine life impacts. At high enough concentrations, the phytoplankton can cause fishkills, a toxic aerosol with respiratory impacts for nearby people, and colored water**.

All of these negatively effect human health and the tourism industry in the area. Our prediction is that this will not occur in the rest of the bloom season, which is from September through November typically, or even into December and January in abnormal years.

In our research, we found that the along-shore wind at Port Aransas, averaged over September, correlated with whether or now a major bloom occurred that year. We found that in years with weaker average winds, blooms were less likely to occur as compared with years with stronger average winds. This was a statistical correlation based on data. To understand why this occurred, we ran numerical drifters with a tool, TracPy, using velocity fields for the Texas and Louisiana continental shelf, as predicted by our numerical circulation model of the area. Our results show that water from south of the Texas coastline in Mexico was connected with the occurrence of a major bloom in Texas waters. We tested this both by running numerical drifters from Mexico, where we think the cells largely originate, forward in time to when and where blooms typically occur in Texas, and backward in time from Texas. Both experiments indicated that southern waters are connected with Texas waters at the relevant time and location for blooms to occur, and, additionally, provided a mechanism for why blooms occur in some years and not in others: when the winds are strong enough, the phytoplankton that would otherwise form a major bloom are instead swept away.

Our prediction index (below) shows distinct behavior in September winds as to whether a major bloom will occur or not. The code I wrote to analyze this data and generate the plot is freely available.

The major blooms discussed here occur at high concentrations of K. brevis, and can lead to fish kills, toxic aerosols, and colored water due to the resulting major blooms. However, even low concentrations of this phytoplankton can cause closures of bays to shellfish harvesting because shellfish filter the water and aggregate the phytoplankton's toxin if it is present. The concentration of cells doesn't have to be very high before the shellfish cannot flush out the toxic cells at a fast enough rate to stay clean. This is why the bays are closed at much lower concentrations of K. brevis than would typically be necessary for a fish kill to occur, for example.

Fortunately, to address the shorter time scale question of this lower level of cell concentration, Lisa Campbell at Texas A&M has an Imaging FlowCytobot to test the water at Port Aransas, TX, regularly and report when K. brevis cells are present. In fact, results from the Cytobot recently indicated low levels of the phytoplankton, close to what could lead to bay closures. However, our prediction suggests that while these low levels of cells may occur (and can't be predicted by our index), they will not massively increase to a high level and therefore there will not be a severe bloom this year.

** Image from Texas Parks and Wildlife Department